Menu

Mushrooms seem to be in everything these days, including varieties once considered exotic, like cordyceps, lion’s mane, and reishi. You may have noticed that more and more food, dietary supplements, drinks, and even skincare products contain a wide range of functional mushrooms.

Among the most popular functional mushrooms is chaga (Inonotus obliquus (Fr.) Pilát). Consuming chaga mushrooms is believed to boost the immune system, maintain blood sugar levels, regulate digestion, and other positive interactions with the human body.

The health benefits chaga mushrooms bring to the table have been touted for centuries. Thanks to modern research and scientific methods, we can now confirm the varied positive impacts this adaptogenic fungus can have on the body.

If you think taking chaga mushrooms can contribute to your wellness, this guide will walk you through the health benefits chaga mushrooms can offer.

Although people will generally refer to it as “chaga mushroom,” chaga is NOT actually a mushroom.

What we call chaga is the common name for a sterile conk or canker that forms after a hardwood tree (usually birch) has been infected by the parasitic fungus Inonotus obliquus (or I. obliquus).

As a parasite, I. obliquus has a one-sided relationship with its host tree. Its enzymes cause the simultaneous decay of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (the three main biological constituents that make up the wood of trees) from the heartwood of the living host.

The breakdown of the heartwood weakens the tree’s infrastructure, allowing for the first traces of what we call “chaga” to protrude from within the tree. This dark conk consists primarily of wood lignans and fungal mycelium (the fungal root structure).

Chaga Facts: Learn more about how chaga grows and where it can be found by reading our article, “What Trees Does Chaga Grow On?”

The chemical composition of chaga was first studied by German-born chemist and pharmacist Johann Georg Noel Dragendorff in 1864. Since then, scientific analyses have revealed over 200 different bioactive metabolites.

Many of these metabolites can support human health, including:

Of all these, the polysaccharides are the most active compounds in chaga.

Polysaccharides are large molecules made up of many simple sugars (monosaccharides). The most important polysaccharides found in chaga are the (1>3)(1>6) beta-D-glucans.

Beta-glucans from functional mushrooms like chaga provide unique opportunities for the discovery and development of new therapeutic agents. In recent years, beta-glucans have received much attention due to their many health benefits, such as immunomodulatory, hepatoprotective, and antioxidative activities [2].

Chaga contains high levels of melanin, giving it the potential to help mitigate radiation-induced damage in these demographics.

Melanin is a skin pigment in mammalian skin, hair, eyes, ears, and the nervous system. It provides a wide range of health benefits, including protection against UV radiation and oxidants (free radicals).Fungal melanin, in particular, has powerful antioxidant and DNA-protective properties, as demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo animal studies. In one study, melanin in wood ear, a black-colored mushroom, protected 80% of mice from a lethal dose of radiation [3].

Chaga and its unique triterpenes have anti-viral properties, as shown in animal and cell studies [48,49].

Chaga contains several types of triterpenes, the most important being inotodiol, a triterpenoid found only in chaga. Inotodiol has also shown immunomodulatory and antioxidant effects [5,6].

Two other notable triterpenes—betulinic acid and its precursor, betulin—are found in birch bark, where chaga gets these compounds. Betulin and betulinic acid have demonstrated antioxidant, anti-ulcer, anti-gastritis, and immunomodulatory effects.

Betulinic acid may help decrease atypical cell growth and is theorized to work by supporting the mitochondria (the parts in each of our cells that help with energy production) [46].

Historically, chaga has been used to provide a wide range of health-promoting effects.

Here are nine potential health benefits of the so-called “king of mushrooms”:

Chaga can boost oxidative phosphorylation to support adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production without leading to heavy oxidative stress.

Humans, like many other organisms, need oxygen to live. Without oxygen, mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells, would be unable to produce the chemical energy or ATP needed to fuel biological processes in the body.

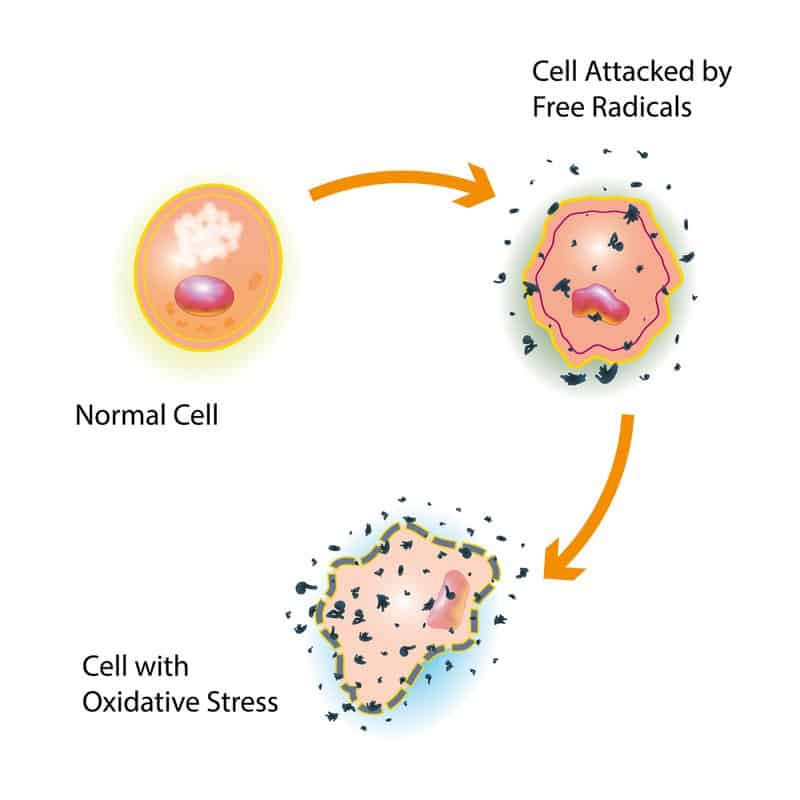

While oxidative phosphorylation is an essential process, it also produces cell-damaging free radicals. Various factors like stress, diet, and environmental exposure can result in a surplus of free radicals compared to the anti-oxidants that would combat them. This imbalance is referred to as “oxidative stress.”

Dangers of Oxidative Stress: Severe oxidative stress can damage cell components (including DNA), cause cell death (also known as inappropriate apoptosis), and disrupt cellular signaling. It can also lead to premature aging and the development of many age-related ailments and conditions.

Chaga produces an impressive array of metabolites capable of acting as potent free radical scavengers. The metabolites in chaga mushrooms benefit DNA health by protecting it from oxidative stress damage.

One study demonstrated that human blood cells pretreated with chaga mushroom extracts before exposure to the free radical H2O2 showed 40% less DNA damage than those that weren’t pretreated [7].

Chaga ranks very high on the Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) scale, which measures antioxidant power.

However, ORAC values came under scrutiny in 2012 when the USDA removed its ORAC Food Database, citing that the test did not directly correlate to health benefits (i.e., higher is not necessarily better) and that ORAC values were being misused by food and supplement ingredient suppliers to promote their products.

Chaga is a source of trace minerals like zinc, copper, iron, and manganese, which can stimulate the production of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in cells. SODs are enzymes that form the first line of antioxidant defense against damage caused by free radicals.

There is some concern that oral administration of SODs is not effective because they are degraded before they can get absorbed into the bloodstream. Still, there have been studies demonstrating the efficacy of oral SOD supplementation [8-10].

Consuming chaga mushrooms has been revered in folk medicine for centuries to encourage gastrointestinal health and digestive comfort.

Modern research confirms that chaga mushroom benefits include gastroprotective properties with the capacity to help regulate the gut microbiota. For instance, alcohol extracts of chaga helped protect the integrity of the stomach wall when given to rats at 200 mg/kg [11].

In another study, mice were fed alcohol chaga extracts at 50 and 100 mg/kg body weight. The results showed that by regulating the release of cytokines, chaga supported the health of the colonic mucosa [12].

The antioxidant activity of polysaccharides in chaga supported pancreatic health and regulated gut microbiota composition and diversity in mice studies [13,14].Chaga supplementation in patients with Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD) showed decreased damage to human lymphocytes [47].

The antioxidant range in the chaga mushroom benefits the body by supporting a healthy inflammation response.

Inflammation is the immune system’s primary response to various triggers, such as toxic agents and foreign invaders. It is also part of the body’s natural healing process.

Your body releases inflammatory chemicals to help mitigate cell damage and to restore tissue homeostasis. However, interrupted or prolonged inflammation cascades can create body damage and disease.

Chaga appears to modulate the release of certain cytokines involved in inflammation [15]. It also appears to be an inhibitor of nitric oxide (NO) and COX-2 in rats, which may explain its ability to alleviate temporary discomfort [15,16].

Chaga is a highly popular adaptogen that affects the body’s immune function.

You may have read or heard the term “adaptogen” or biological response modifier (BRM) when discussing certain herbs and functional mushrooms. As the name implies, BRMs are substances that can modulate the immune system’s response by either turning it up or down.

An adaptogen is a type of BRM that must meet the following three criteria [17]:

Essentially, adaptogens help your body adapt to stress and maintain balance.

As an adaptogen, chaga mushroom benefits overactive immune systems in certain demographics by providing balance in immune health response. Initidiol, a triterpenoid unique to chaga, acts as a mast cell stabilizer and can support eye and nasal comfort in mouse models [18].

While the immune system is designed to protect the body against foreign invaders, it can also create discharge symptoms. This response can affect the eyes, sinuses, and lungs, usually showing up as mucus, pain, or inflammation.

Watch Allergy Symptoms: Allergies aren’t always harmless. Some individuals may experience anaphylactic shock—a severe and sometimes life-threatening allergic reaction.

Chaga can promote the secretion of certain cytokines to modulate immune responses in mice [19]. A new animal study also showed that chaga mushroom extracts prevented chemically induced immune system overreactions, demonstrating its potential as a useful functional food [20].

Other studies have shown that the active compounds in chaga may have selective activity against many types of malignant cells, specifically in relation to the inhibition of p38 kinase and ERK1/2 pathways [21-22,62].

Healthy blood sugar levels are linked to heart, blood vessel, nerve, kidney, skin, and brain health [23]. If you want the answer to “can chaga lower blood sugar levels?”, it’s a bit more complicated than you might think.

Regarding blood sugar, chaga mushrooms are believed to maintain balanced blood sugar levels. Consuming chaga mushrooms can be beneficial for people with insulin resistance or polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

Insulin is the hormone responsible for moving glucose in the bloodstream into your muscle and fat cells to be stored for energy production. However, some people may develop insulin resistance from certain conditions (e.g., obesity, type 2 diabetes, etc.), which makes it challenging to regulate blood sugar levels.

When it comes to regulating cholesterol, chaga mushrooms have shown evidence in studies of potentially managing cholesterol imbalances in the body. This makes chaga a beneficial supplement for people struggling with high cholesterol.

Multiple animal studies suggest that chaga may be able to support balanced blood sugar levels [24-26]. In one study, investigators found that mice fed dry matter chaga extract for three weeks were able to better maintain healthy blood glucose levels as well as total cholesterol, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C, “bad cholesterol”) levels.

Triglyceride and cholesterol imbalances are almost always tied to metabolic health in relation to insulin sensitivity and glucose management. Most notably, the research team found that feeding chaga supported healthy pancreatic tissue in mice (the pancreas is the organ that secretes insulin) [26].

A follow-up research confirmed these effects on blood sugar and cholesterol. Mice treated with either 30 or 60 mg/kg body weight of chaga ethanol extract for 21 days had similar results as in the first study [27].

In another animal study, rats were administered either polysaccharides extracted from chaga (at doses of 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg) or saline (which acted as a placebo) for six weeks. At the end of the study, the rats given chaga were better able to maintain blood glucose levels within healthy limits than the rats given saline, and their pancreatic beta-cells were also healthier [24].

The chaga mushroom benefits for balancing blood sugar may be attributed to the inhibition of an enzyme (alpha-glucosidase) that breaks down starch by its polysaccharides. Blocking this enzyme helps slow down glucose absorption in the digestive organs [28].

Research performed in vitro showed the polysaccharides in chaga inhibit this enzyme, demonstrating that chaga warrants more research into its effects on blood glucose modulation [25]. Based on these results, more clinical data from human studies are needed to advance our understanding of chaga’s relationship with blood sugar.

Chaga is an adaptogen that has the capacity to support allostasis, or stability while undergoing change, in the entire body. This potentially includes your energy levels and muscle endurance, as seen in animal studies.

An animal study showed that chaga may help increase exercise endurance. Mice that were given chaga extracts for 14 days (at 0, 100, 200, and 300 mg/kg) were able to swim for a longer period of time than those given distilled water.

Scientists noted that the mice given chaga also had significantly more glycogen—the predominant storage form of glucose for energy production—in their liver and muscles.

Glycogen storage directly affects exercise endurance, and the results of this study suggest that chaga might help increase the time before glycogen is depleted [29].

Chaga polysaccharides also greatly reduced blood lactate levels in the mice. Muscles produce high levels of lactate during high-intensity exercise, which contributes to fatigue. Therefore, removing lactate quickly is beneficial to prevent or delay muscle fatigue [29].

Additional Chaga Info: For more information on how chaga and other healthy mushrooms can help support exercise endurance, read our article, “Stimulant-Free Pre-Workout & Post-Workout Mushroom Supplements.”

As a folk remedy, chaga extracts are one of the fungi that can be used to boost immune system function.

The immune-supporting activity is believed to be due to the diverse constituents found in chaga, such as [48,49]:

Chaga’s other bio-compounds are being investigated by the scientific community as potential agents to protect the body against variopus foreign invaders [30–35].

Beta-glucans and betulinic acid in chaga may help slow down signs of aging in your skin. Chaga infusions can help comfort irritated skin and reduce redness and dryness.

A case study of 50 people found that after taking chaga for 9 to 12 weeks, individuals experienced improved skin health, as demonstrated by increased skin comfort, smoothness, and moisturization [36].

Melanin also plays an important role in skin health. The melanin found in chaga is believed to protect human skin against DNA damage by absorbing UV radiation. An in vitro study discovered that melanin increased the sun protection factor (SPF) of gel sunscreens [37].

Another study found that melanin functions as a free radical scavenger, which can also help keep your skin looking younger for longer [38].

Oxidative stress is a major contributor to mild memory problems associated with aging.

A team of researchers investigated if chaga had any protective effects in mice with chemically induced cognitive decline. They found that mice given chaga for seven days had significantly improved learning and memory compared to those that did not receive the fungus [39].

When it comes to chaga, understanding the right dosage and being aware of safety considerations and potential side effects is crucial. This will help you maximize the benefits while minimizing any risks.

The typical dosage is 250 to 500 mg of an 8:1 extract two to three times a day [4]. However, the appropriate dose depends on various factors, such as your:

The dosage that works for one person may not work for you. The quality of the chaga extract you use will also significantly affect the health benefits you get.

One animal study used 6 mg/kg of chaga extract per day (the equivalent of 408 mg for a 150-pound person) [40]. That being said, we highly recommend that you start with small doses of chaga and increase slowly over time to the recommended dose.

Chaga extract supplements are generally well tolerated, with few reported side effects. However, it’s important to remember that the studies demonstrating chaga mushroom benefits were performed on cells or animals.

There have been no randomized human clinical studies to evaluate chaga's safety, but there is strong historical evidence of its use in traditional remedies. Therefore, you should consult a health practitioner prior to taking chaga if you have certain health conditions.

The polysaccharides and other substances found in chaga are known to affect blood circulation. For this reason, individuals with bleeding disorders or those on anticoagulants (blood-thinning medications) should exercise caution when considering chaga extract supplements.

This could pose an issue when combined with anticoagulants, depending on the chaga dose. Chaga may also affect blood glucose levels, so monitor your blood sugar levels while using it.

One safety concern stems from the fact that chaga contains oxalates, organic acids also found in vegetables, grains, and fruits. Research suggests that chaga contains anywhere from 2–12% of oxalates, depending on the source.

While oxalates are naturally expelled from the body, some individuals may develop complications from eating a diet high in oxalates. This is because extra oxalates combine with calcium to form kidney stones and crystals [41].

In one published case, a 72-year-old Japanese woman consumed four to five teaspoons of chaga mushroom powder per day for six months (a dose far higher than any recommended by Real Mushrooms).

The source of her chaga extract powder was unclear, as well as whether it was contaminated or an extract. She developed oxalate nephropathy and eventually irreversible renal failure [42].

However, following the guidelines for dosage on Real Mushrooms’ chaga extract powder or chaga capsules will help to avoid over-consumption.

Within the classification of oxalates, there are two forms: soluble and insoluble. Chaga has both forms.

Soluble oxalates are absorbed into the blood and need processing by the kidneys. Insoluble oxalates are bound to minerals and don’t get absorbed or processed by the kidneys [43].

Oxalates are higher in several common foods such as chocolate, grains, nuts, and certain greens (rhubarb, chard, and beet tops). Mushrooms grown with high heavy metal substrates may form calcium oxalates at a higher rate, which is more concerning for kidney stone formers [44].

Generally, wild-harvested chaga has fewer oxalates than cultivated chaga.

Grown for Purity: Real Mushrooms’ chaga is wild-harvested and tested for heavy metals along with other rigorous quality control measures. Additionally, Real Mushrooms powder and capsules are extracts rather than whole powder, which also lowers their oxalate content.

There are no known side effects of taking chaga mushrooms. However, the impact on the immune system and blood sugar levels may cause some complications.

For instance, individuals with a history of kidney stones, a strong antibiotic history, low hydration, or low calcium status should consult a professional before using chaga mushrooms in any form.

You should also think twice about using chaga mushroom products if you have a medical condition or are taking medication that regulates your blood sugar levels (e.g., diabetes medications such as insulin, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, biguanides, etc.) Doing so will prevent the risk of adverse drug interactions.

We highly recommend consulting a health practitioner before taking chaga mushroom supplements if you have any health concerns.

Chaga is a natural product, which means its properties will vary greatly depending on its growing conditions.

Since chaga mushrooms (I. obliquus) are restricted to very cold climates, they’re regularly exposed to freezing temperatures, various pathogenic microbes, and UV irradiation in their natural environment [31]. These harsh conditions contribute to chaga mushrooms’ unique chemical composition.

Concerns about overharvesting chaga have led researchers to try growing I. obliquus in a laboratory. However, attempts have so far been unsuccessful at achieving the diversity and levels of the bioactive compounds found in wild chaga.

Without the birch tree involved in the growing process, betulin and other important compounds will not be present. One study noted that the immuno-stimulating effects of lab-grown chaga only reached about 50% of those of wild chaga [31].

Another evaluation found that wild and cultivated chaga differ greatly in chemical composition.

Wild chaga contained diverse sterols, with 45.47% lanosterol, 25.26% inotodiol, and ten other sterols comprising the remaining 30.17%. In comparison, the cultured chaga only contained three sterols, with ergosterol being the predominant sterol at 82.20% [45].

Research is ongoing to improve chaga cultivation techniques. Currently, in Finland, birch trees are being inoculated with chaga in order to cultivate it directly on the host tree.

It’s clear that many of the chaga mushroom health benefits are a result of its years-long struggle for survival in harsh environments where it thrives.

When choosing your chaga extract supplement, it’s important to know where the product is sourced. Because chaga grows so slowly, it can accumulate a high level of toxins from pollutants in the air.

It’s for this reason that Real Mushrooms only uses wild-harvested organic chaga from Siberia to ensure the highest purity extracts possible. Real Mushrooms Organic Siberian Chaga is extracted using hot water, which pulls out all water-soluble compounds like beta-D-glucans.

There are many ways to benefit from chaga mushrooms for health support, especially by taking them as chaga mushroom supplements.

Keep in mind that the effects of adaptogens like chaga are cumulative. For the best results, take chaga consistently to help your body resist occasional stress and support your immune system.

Chaga has traditionally been consumed as tea in Finland, Russia, and other countries. Raw chaga chunks can be soaked in hot water, which acts as an extraction agent for all the nutrients from the chitinous interior of the chaga.

If you live in the Northern part of the world where chaga grows naturally, you have the opportunity to harvest this fungi to make homemade chaga tea.

The most accessible way to make chaga tea is by using a high-quality pure chaga extract like the Real Mushrooms Chaga Extract powder. The hot water extraction method used for our chaga products ensures a higher concentration of beneficial bioactive compounds.

It’s also more economical—the amount of powder needed to make the tea is much smaller than using actual chaga chunks.

Chaga Tea Recipe: For our chaga tea recipe, read our article, “How to Make Chaga Tea and 9 Other Chaga Recipes.”

If you’re always on the go, you probably don’t have time for elaborate recipes. That’s why Real Mushrooms has produced an Organic Siberian Chaga Extract in capsule format. Just two capsules a day provide 1,000 mg of chaga extract with over 8% beta-D-glucans.

For coffee drinkers or those who prefer powder, our Organic Siberian Chaga Extract in powder format may be the perfect choice for you. To many, chaga tastes slightly bitter and earthy, making it a complementary flavor profile to your morning coffee or your evening hot chocolate.

Here are the top four things to remember when purchasing a chaga supplement to get the most health benefits for your dollar:

As with any dietary supplement, don’t forget to consult a healthcare professional before using chaga supplements to prevent drug interactions with anticoagulant drugs and other forms of medicine. Being transparent to your healthcare provider regarding your health concerns is an effective way to maintain your wellness and overall health.

Chaga mushrooms have great potential to improve your overall health. With its various health benefits that can boost immune health support, blood sugar regulation, cognitive function, taking chaga can be a great way to reach your wellness goals.

To begin experiencing the potent health benefits of chaga mushrooms, try one of our 100% organic chaga powders or organic chaga capsules extracted straight from fruiting bodies.

Check out our wide selection of 100% organic chaga mushroom supplements today! Let us know if you fell in love with these special functional fungi like so many of our other customers!

*Disclaimer: The statements made in this article have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Any products mentioned are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The information in this article is intended for educational purposes. The information is not intended to replace medical advice offered by licensed medical physicians. Please consult your doctor or health practitioner for any medical advice.

Disclaimer: The information or products mentioned in this article are provided as information resources only, and are not to be used or relied on to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. This information does not create any patient-doctor relationship, and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment. The information is intended for health care professionals only. The statements made in this article have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Any products mentioned are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The information in this article is intended for educational purposes. The information is not intended to replace medical advice offered by licensed medical physicians. Please consult your doctor or health practitioner for any medical advice.