Menu

In This Article

With plenty of articles out there touting the magic of chaga, we decided to focus on many of the unknown aspects or myths about it. What is Chaga? It is a very unique parasitic fungus, which is much different from the other mushrooms you know and love.

In the late 1990s, Chaga mushrooms were virtually unknown as a dietary supplement, with the exception of Russia and a few countries in Southeast Asia. Now, in today’s world, many circles highly regard Chaga as a potent super food.

So let’s jump right in and reveal 9 things you didn’t know about Chaga.

If you'd prefer to get your Chaga facts from the mouth of Real Mushrooms' Chief Funguy, Skye Chilton, take a look at the video below:

So, what exactly is Chaga, you ask?

Chaga is the common name for a perennial canker or sterile conk that commonly forms on birch tree trunks (Betula papyrifera, paper birch) after it has been infected and colonized by the mycelia of the pathogenic fungus Inonotus obliquus. The part of this fungus that one harvests is the outward manifestation of the fungal disease.

Common names for Chaga include clinker polypore, tinder conk, cinder conk, or birch canker polypore (not to be confused with birch polypore - Fomitopsis betulina). In British Columbia, Inonotus obliquus is classified as a tree disease.

What we call ‘Chaga’ is the dense black mass that can be seen on the exterior of trees (almost exclusively on birch trees) infected with the fungus Inonotus obliquus. It's not a mushroom (fruiting body) but a dense sterile mass of decayed bits of birch tissue with mycelia incorporated.

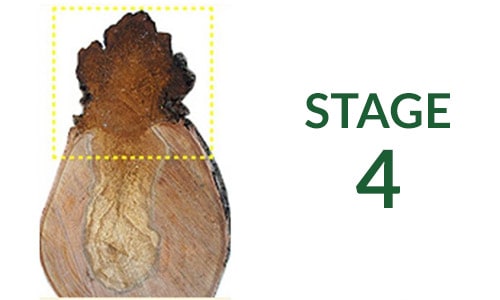

When chopped from the birch tree, the interior has a rusty yellow-brown color, is somewhat granular in appearance, and is often mottled with whitish or cream-colored veins. Chaga can be referred to as a sclerotium, which is a dense mass of mycelium, but this is technically incorrect as Chaga is not pure mycelium.

Research is needed to fully understand the exact composition of Chaga. One research paper estimated Chaga to be only around 10% mycelium based on microscopic observation. A more accurate term for Chaga is conk or canker or just plain old Chaga.

The exterior canker that is harvested should not be confused with the actual fertile mushroom (fruiting body), which normally forms under the partially detached bark on dead-standing or fallen trees.

This fruiting body is a greyish, flat thin-layered mass, up to 3-4 meters long and 40-50 cm wide, with downward cascading pores, which are the spore-producing layer of polypore fungi.

The bark has peeled away, revealing the porous fruiting body. ©Terhi Joki, KÄÄPÄ Biotech, Finland.

The bark has peeled away, revealing the porous fruiting body. ©Terhi Joki, KÄÄPÄ Biotech, Finland.

Chaga is a slow-growing fungus that primarily grows on birch trees. It is commonly found in the boreal forest regions of the Northern Hemisphere like in Russia, Korea, Eastern and Northern Europe, Northern areas of the United States and Alaska, Canada, and Northern China.

Typically, one finds well-developed Chaga sclerotia on trees over 40 years of age, but the infection starts earlier. The period from initial infection to tree death varies with the number of infection sites and tree resistance but is typically around 20 years. After about 3-5 years of growth, the Chaga begins to reach a harvestable size.

The harvested dark black conk consists primarily of wood lignans from the host tree and mycelium of the invasive fungus. Due to this, when Chaga grows on birch, it will also contain birch compounds like betulin and betulinic acid [4].

After harvesting, dried Chaga can regrow to harvestable size again in three to ten years, and this can be repeated until the tree dies. Chopping off the dry Chaga does not kill the organism, and the mycelium is still inside the tree, slowly consuming it.

Chaga is not technically a perennial by definition; it may live for years as it consumes its food source, but once that source is exhausted, it will then die for lack of nutrients.

Russians have known about Chaga’s health benefits for a long time; the word ‘Chaga‘ is a derivative from ‘чага‘, which is the old Russian word for mushroom. A healing plant of renowned value throughout the world, Chaga is thought to be a potent immune-stimulating functional mushroom.

In fact, the first verifiable mentions of Chaga were from the early 16th century. Chaga is documented in folk and botanical remedies throughout Eastern Europe. Traditionally, consuming Chaga may help with stomach discomfort and overall digestive health [1].

Chaga became popular in the West after it was mentioned in the book Cancer Ward by Nobel Prize-winning Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. In the book, he notes that poorer people saved money on tea by brewing Chaga.

As early as 1955, a Chaga extract known as Befungin (Russian translation) has been sold in Russia to treat stomach and intestinal ailments.

Smaller chunks of chaga cut from a larger piece.

Smaller chunks of chaga cut from a larger piece.

Chaga also contains melanin, concentrated in the black outer crust, which is a complex compound that gives the skin, hair and the iris (colored part of the eye) their color. Our skin naturally darkens in response to sun exposure which stimulates melanocytes to produce melanin.

Considered a potent source of melanin, Chaga may help protect the skin and hair from sun damage. Melanins have a role in DNA repair, mitochondria health, cell metabolism, and protection from light and radiation.

In particular, melanins from mushrooms exhibit a healthy inflammation response based on their antioxidants and gene-protecting properties. Melanins can decrease oxidation of fatty acids and damage of membranes creating lots of potential for skin health [8, 9].

Often, Chaga is compared to coffee with its robust flavor and dark color. It’s earthy, slightly bitter, and has a small hint of forest sweetness. Luckily, if you are sensitive to caffeine, Chaga is a great alternative to coffee as it’s caffeine-free, so it won’t keep you awake and it’s just as tasty!

In Finland, during WW2, there was a coffee shortage, and substitutes started popping up, many of which were based on roasted rye [3]. It was then that Chaga emerged as an ideal coffee substitute known as Tikka Te.

Chaga Coffee (which is really more like a tea) is a great and simple way to consume Chaga. You can buy the wild chunks from a reputable source to brew your own magical concoction.

But if you’re just looking for a quick and easy way to add Chaga to your diet, we’ve made it simpler for you to consume with our amazing Chaga capsules.

We use a hot water extraction method made from our pure source of wild-harvested Chaga from Siberia. Take two of these capsules daily over a three-month period to feel the full health benefits.

Many argue that wild harvesting of Chaga is not sustainable, and we need to be wary of overconsumption of this fungi.

In 2004, David Pilz, Forestry Mycologist at Oregon State University, went to Russia to report on whether Chaga harvesting in Russia was sustainable or not [5]. This is the most detailed report of Chaga harvesting currently available. The report determined that the “biological Chaga resource is immense, and unlikely to be over-harvested to the detriment of the species Inonotus obliquus any time in the near future.” According to the report, Chaga is excessively abundant, even with over-harvesting estimates.

The report states that Chaga infects upwards of 20% of all birch trees in Russia. This is in stark contrast to some claims on the internet that Chaga is extremely rare and only found on 1 in every 10,000-20,000 birch trees.

Similar to Russia, Scandinavia has vast boreal forests. Luke, The Natural Resources Institute Finland, estimates that Chaga infects 6-30% of all birch in Sweden and Finland [4].

Given similar estimates between Russia, Finland, and Sweden, it would be safe to assume that Canada also has vast amounts of Chaga in its boreal forest regions.

The Pilz report did make an important note about proximity to Chaga. While the resource is vastly abundant, how far harvesters need to travel in order to find chaga will have a direct impact on the selling price. Popular harvesting areas may get over-harvested and lead people to believe that this fungus is threatened.

In the future, there may be a tipping point at which the cost of harvesting becomes too expensive for supplements but given the vast amounts of Chaga available, this turning point would be well before there was any threat to the species itself.

An important note is that harvesting Chaga does not kill the organism itself. The mycelium is still inside the tree, slowly consuming it.

Near or after the tree’s death, the mycelium will begin to produce the mushroom (fruiting body) so that spores can be released and the organism can reproduce. Chaga harvesting does not impact the organism's ability to reproduce.

Since the harvested part of the Chaga is actually a woody canker and not a mushroom in the traditional sense, it begs the question: Does Chaga have a fruiting body?

Yes, it does, but we rarely see it.

The actual mushroom (fruiting body) forms under the bark of dead-standing or fallen trees. After the tree dies, the bark slowly separates from the tree, revealing the sporocarp (fruiting body). This mushroom (fruiting body) is a greyish, flat thin layered porous mass with downward cascading pores.

When the conditions are correct, the pore layer will begin to release spores which will get blown around in the wind and eventually end up on weakened birch trees and the infection process will start over.

Insects also like to eat the mushroom which helps to transport the spores to new areas.

Cultivated Chaga can and will have a different composition and therapeutic properties, depending on the conditions under which it grows (different types of substrate, environmental conditions, etc.)

This is because a lab can only cultivate the mycelium and not cultivate the canker or sclerotium itself.

Wild Chaga takes three to five years before it can be harvested, and many of the special compounds in Chaga, like betulin and betulinic acid, come from the birch tree. If no birch tree is involved, like a lab-grown process, then none of these important birch compounds will be present.

No black outer layer, no melanin. Not to mention that lab-grown Chaga is myceliated grain so there will be a large concentration of grain in the final product as opposed to the actual Chaga canker.

Luckily, our Siberian Chaga is wild-harvested and tested by 3rd party laboratories for active compounds like beta-D-glucans that are quintessential nutrients for the immune system. This wild Chaga has been maturing for upwards of 20 years in the cold and wild boreal forests. Siberian Chaga contains many polysaccharides, triterpenoids, and melanin which is a pigment we need throughout the human body.

We care deeply about sourcing the highest quality mushrooms that contain the most functional compounds to support your health over long term use. It is recommended that adults take two capsules of our organic Chaga daily.

The bushcraft and survivalist communities use Chaga as a fire starter. Once dried, the inner brown section of chaga can take a spark, and it is very slow burning making it ideal as starting coal for your fire.

Fire pistons, which compresses air to create heat to ignite your starting coal, can also make use of Chaga.

You’ve just learned that:

At Real Mushrooms, we pride ourselves on our product quality, as we know products on the market today aren’t always what they seem. We offer transparency with our sourcing, processing, and ingredients.

We always use 100% mushroom extracts made with no grain or filler, created with ethics and purity, to assist in bringing optimum health to your life.

If you’d like to understand the extraction methods for mushrooms click here. This article explores whether dual extraction is necessary.

How did you enjoy the article? Did you learn anything new? Please tell us your special experiences with Chaga in the comments below!

It's one of our team's favorites!

Directions: Bring all of these ingredients to a simmer on the stovetop, serve, and enjoy a cup of Chaga! Add a few cacao nibs at the end for an added crunch. This will give you a super boost of nutrients and energy!

For more recipes like this, be sure to visit our mushroom recipe section of the blog.

There are so many ways to incorporate this superfood into your daily regime. Add our Chaga powder to your smoothies, and oatmeal, as an added nutrient to your morning coffee or tea, or even into your raw desserts.

Disclaimer: The information or products mentioned in this article are provided as information resources only, and are not to be used or relied on to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. This information does not create any patient-doctor relationship, and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment. The information is intended for health care professionals only. The statements made in this article have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Any products mentioned are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The information in this article is intended for educational purposes. The information is not intended to replace medical advice offered by licensed medical physicians. Please consult your doctor or health practitioner for any medical advice.